Complementary alternative medicine (CAM) and treatments have received much attention and acclaim in the past years. Many patients and practitioners turn to CAM as alternatives to avoid side effects of drug therapies, as well as enhance personal beliefs about Eastern medical options. Of particular interest is the use of acupuncture as an alternative to conventional medical treatment.

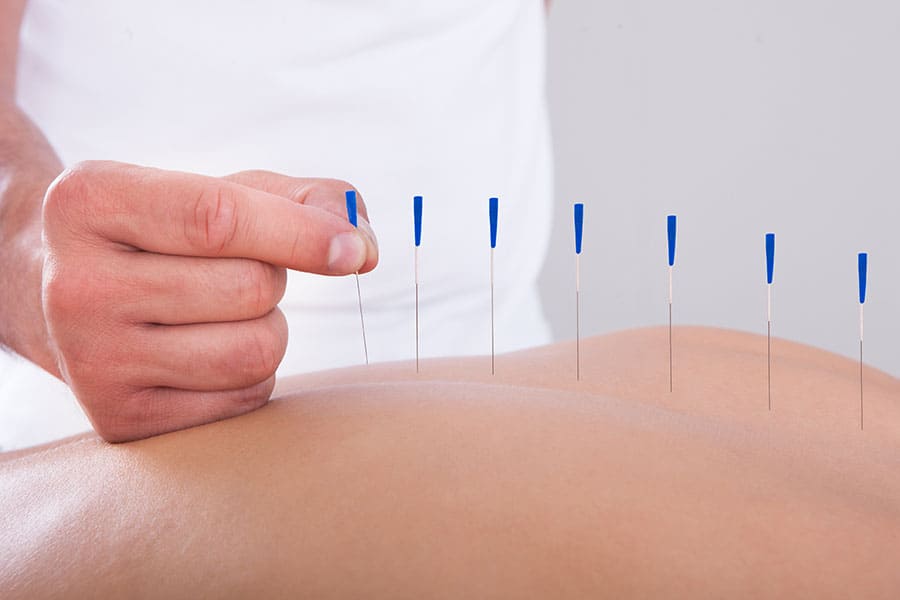

Acupuncture is a type of traditional Chinese medicine that has been generating much interest in the United States for the past few decades; there are acupuncturists who strictly practice traditional acupuncture, those who practice broad Eastern medicine that includes acupuncture, and Western medical doctors who additionally blend acupuncture within their practice. This technique, which originated in Asia thousands of years ago, involves stimulating specific points of the body with thin needles to affect the body’s physical functions.1

The procedure of inserting thin needles into the skin with the intention of not actually penetrating specified acupuncture points and unsystematically is referred to as sham acupuncture.2 Sham acupuncture is often utilized as a placebo for research into the effectiveness of traditional acupuncture, even though there have been a lot of contradictory and inconclusive findings in comparing the efficacy of both. Controlled clinical trials in Germany between 2002 and 2011 compared results of traditional acupuncture as well as four different methods of sham acupuncture. Thirty seven out of 57 studies demonstrated that true acupuncture was more therapeutic than sham acupuncture methods; however, the authors did not think there was sufficient evidence to make a conclusion and recommended improved methodology in future research.3

Chronic Pain, Headache & Fibromyalgia

The sensation of pain is the body’s way of signaling danger or damage. Throughout the body, there are nerve endings that act as pain receptors, or nociceptors, which signal actual or perceived damage.4 Pain can be categorized in many different ways, depending on the cause, locality on the body, quality or description of the pain, and so on; most often it is classified as being either acute or chronic. Pain is subjective and personal, and pain has a negative impact on overall quality of life. There have been many studies conducted in regards to acupuncture’s utility in treating various kinds of pain, and evidence suggests it does aid in relieving certain types of chronic pain.

SEE ALSO: Trigger Point Therapy

The results of a randomized trial, published in the Archives of Internal Medicine, demonstrated that, while we do not know the specific mechanisms at work, patients suffering from chronic low back pain experience less back-related dysfunction after being treated with standardized, individualized and even simulated acupuncture than with their usual care.5 In October 2009, the Cochrane Collaboration performed systematic reviews of trials that studied the effects of true and sham acupuncture on the prevention of both migraines and tension-type headaches. They found inclusion of either method of acupuncture in the patients’ care led to a decrease in frequency of both types of pain, although for tension-type headaches the results were slightly better when true acupuncture was used.6,7 Another review by the Cochrane Collaboration, published in 2013, summarized the effects of acupuncture with and without electrical stimulation, as well as sham acupuncture, on various symptoms of fibromyalgia. Acupuncture was also studied as an adjunct to pain medication and in place of antidepressants. Although viewed by the authors as incomplete and a relatively small study, the research was overall encouraging in demonstrating improvement of symptoms when patients were treated with acupuncture with electrical stimulation.8

Other high-quality randomly controlled trials involving individual patient data indicated that, in regards to osteoarthritis, and chronic headache, back, neck and shoulder pain, patients did experience relief after receiving acupuncture and therefore it should be considered as a real treatment option.9 However, since there was only a modest difference between the effectiveness of acupuncture and sham acupuncture, there appear to be other factors involved in addition to the position of the needles alone. These studies suggest that, regardless of how it works, the use of acupuncture appears to have a healing effect in regard to the above-mentioned types of pain and, therefore, is as valid an option as other currently prescribed pain treatments.

Use of Acupuncture on Nausea/Vomiting

Research has also been conducted in regards to whether acupuncture, and variations of it, such as acupressure and electroacupuncture stimulation, are useful in relieving nausea. A review by the Cochrane

Collaboration of 40 randomized trials discussed the efficacy of stimulating the pressure point P6, on the inner wrist, in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Multiple variations of acupuncture were studied and compared to the use of antiemetic drugs; overall the P6 pressure point stimulation was found to be comparable to antiemetic medications in regards to effectiveness.10 Patients experiencing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting have increasingly been offered acupuncture and acupressure as complementary treatment, and many studies have looked into the efficacy of these therapies.11 These studies again are examples of the validity of acupuncture, and how it can and ought to have a place alongside more conventional treatment options.

Risks of Acupuncture

As with most, if not all, medical treatments, there are potential complications associated with acupuncture. A systematic review of Chinese literature on adverse events associated with acupuncture treatment was published by the World Health Organization. It portrays a variety of events, ranging from hemorrhages to pneumothorax to bacterial infection; the review found that most of these were associated with “inappropriate technique,” such as aseptic methods and improper placement of needles.12

The review states remaining incidents are mostly minor and are preventable, with the example of the patient’s physical condition and positioning leading to a fainting episode. Similarly, the Mayo Clinic website describes “the risks of acupuncture are low if you have a competent, certified acupuncture practitioner.”13 It also points out certain conditions should be considered as contraindications for patients to receive acupuncture, such as bleeding disorders, use of a pacemaker and pregnancy. Both articles demonstrate that what we value and consider in regards to getting other types of medical treatments should likewise be recognized in regards to acupuncture: competence, professionalism and awareness of side effects and contraindications.

The future promises continued research into the various potential uses of acupuncture, with consideration of even more diverse areas of use and a push toward larger-scale, more controlled studies. There are also growing alternatives for acupuncture itself, with the use of electro-acupuncture, acupressure, laser acupuncture and so on. Acupuncture treatment is showing promise in relieving some conditions; for others we cannot yet determine whether it is comparable to currently used alternatives; for still other pain and disease processes, research is not showing any evidence it is useful. Several conclusions can be made; it is clear that for nurses and practitioners to better understand the role and benefits of acupuncture additional research is needed, and it would be helpful for there to be more control over extraneous variables and for studies to be on a larger scale. Second, if patients report they feel better after this treatment, and if there is no greater risk in it than in conventional or alternative treatments, then it is reasonable to allow them to use it. Consequently, in terms of cost and insurance coverage, acupuncture ought to be available patients who might seek to utilize it.

For more information, visit the websites of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the National Institute of Health, the Mayo Clinic and World Health Organization.

References

1. Acupuncture: An Introduction. National Institutes of Health – National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. http://nccam.nih.gov/health/acupuncture/introduction.htm Published December 2007, Updated September 2012. Accessed June 29, 2014

2. Integrative Medicine: The Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration. Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. http://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/acupuncture-trialists-collaboration Published 2014, Accessed June 29, 2014

3. He, W, Tong, Y, Zhoa Y, Zhang, L, Ben, H, Qin, Q, Huang, F, Rong, P. Review of controlled clinical trials on acupuncture versus sham acupuncture in Germany. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2014; 33(3):403-7.

4. Dubin, Adrienne E, Patapoutian, Ardem. Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010; 120(11):3760-3772.

5. Cherkin, Daniel C, Sherman, Karen J, Avins, Andrew L, Erro, Janet H, Ichikawa, Laura, Barlow, William E, Delaney, Kristin, Hawkes, Rene, Hamilton, Luisa, Pressman, Alice, Khalsa, Partap S, Deyo, Richard A. A randomized trial comparing acupuncture, simulated acupuncture, and usual care for chronic low back pain. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009; 169(9):858-866. Retrieved from

6. Linde, K, Allais, G, Brinkhaus, B, Manheimer, E, Vickers, A, White, A.R. Acupuncture for tension-type headaches. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD007587. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007587.

7. Linde, K, Allais, G, Brinkhaus, B, Manheimer, E, Vickers, A, White, A.R. Acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD001218. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001218.pub2.

8. Deare, JC, Zheng, Z, Xue, C.C.L., Liu, JP, Shang, J, Scott, SW, Littlejohn, G. Acupuncture for Fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD007070. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007070.pub2

9. Vickers, AJ, Chronin, AM, Maschino, AC, Lewith, G, MacPherson, H, Foster, NE, Sherman, KJ, Witt, CM, Linde, K. Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2012; 172(19):1444-1453.

10. Fan L TY. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009; Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003281. Retrieved from http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD003281/p6-acupoint-stimulation-prevents-postoperative-nausea-and-vomiting-with-few-side-effects

11 Garcia, MK, McQuade, J, Haddad, R, Patel, S, Lee, R, Yang, P, Palmer, JL, Cohen., L. Systematic review of acupuncture in cancer care: a synthesis of the evidence. Journal of clinical oncology. 2013; (7):952-60.

12. Zhang, J., Shang, H., Gao, X., Ernst, E. Acupuncture-related adverse events: a systematic review of the Chinese literature. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010; 88: 915-921C. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/88/12/10-076737/en/

13. Mayo Clinic Staff. Acupuncture: Risks. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/acupuncture/MY00946/DSECTION=risks

Melanie Bal is a staff RN in the Acute Elder Care Unit at Hackensack University Medical Center, Hackensack, N.J., and Margaret Quinn is clinical associate professor

Division of Advanced Nursing Practice, both at Rutgers University.