Osteopenia and Osteoporosis are two conditions related to bone loss that can develop as a result of poor habits early in life

As young children and teens, few of us would consider that activities of daily life could have a significant effect on our bone “bank accounts” in later years, adding hefty deposits or woeful withdrawals to the amount of bone mass we would need in subsequent years. We were too busy worrying about becoming young adults, hanging with friends, and participating in activities that enriched our lives. Yet the types of activities we chose, and the foods we consumed may have had far-reaching implications well past the teen years, leaving us with a bone bank account that was perilously close to being overdrawn. Such an overdrawn account could potentially lead to conditions such as osteopenia and osteoporosis.

Bone Mass

“Peak bone mass” tends to be higher in men than women, although prior to puberty, both sexes acquire bone mass at approximately the same rate. Genetic factors (gender, ethnic background) may account for up to 75% of acquired bone mass, but environmental factors (such as those attributed to exercise and diet) account for the remaining 25%. African Americans of both sexes tend to have higher bone densities than Caucasians, although the reasons are unclear. The amount of bone mass can keep growing in the human skeleton until late into the 30’s, although up to 90% of “peak” bone mass is typically acquired in females by age 18 and by age 20 in males.1

Prior to this time, a diet rich in calcium as well as a lifestyle that includes plenty of weight-bearing exercise will produce strong healthy bones for years to come. A teenage lifestyle that is fixated on dieting, smoking, and sedentary activities would be one that could lead to osteopenia or osteoporosis in later years, for both females and males.1

Defining Bone Health

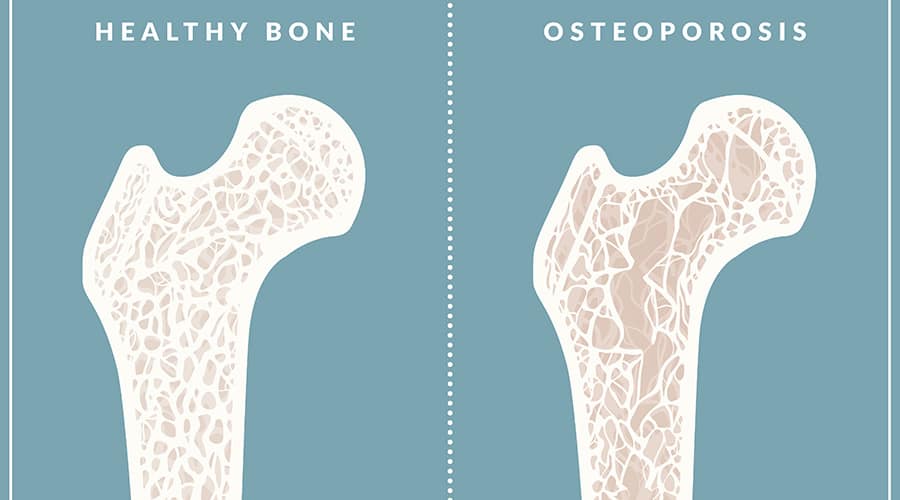

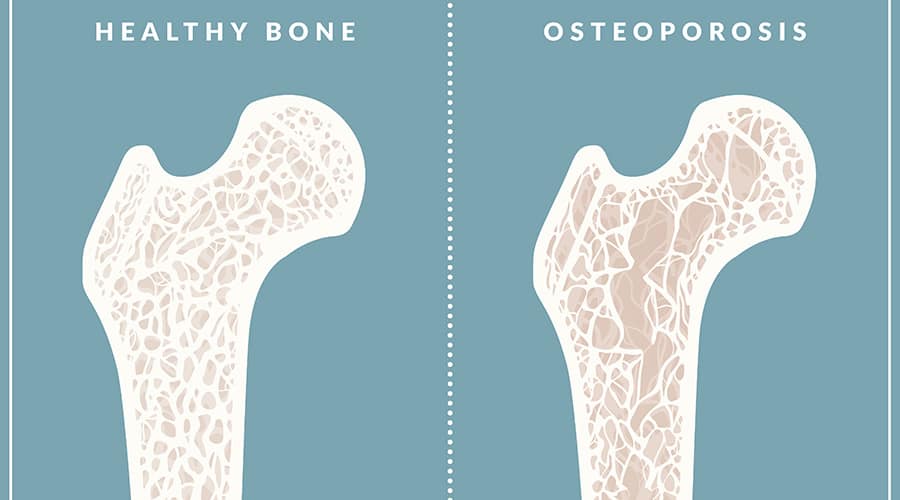

Osteopenia and Osteoporosis are both terms related to degrees of bone loss, or terms defining bone mineral density, which describes the strength of a bone and the degree with which it may resist fracture. Bone mineral density scores have often been described as a mountain slope, with normal being the top of the mountain, and osteoporosis “landing” at the bottom of the slope. Osteopenia, which affects approximately 50% of Americans over the age of 50, would be located halfway down the slope of the mountain.2

Everyone’s bones weaken as they age, but behaviors that are performed daily will have a significant impact on bone health. Habits that may accelerate bone loss and weaken bones, leading us further down the slope towards porous bones would include the following:

-

- Not engaging in enough weight-bearing exercise (at least 30 minutes/day): walking, jogging, running.

- Smoking cigarettes

- Drinking alcoholic beverages

- Not getting enough Vitamin D or calcium

- Taking medications such as anticonvulsants or corticosteroids

- Having rheumatoid arthritis or being a transplant survivor4

Although women are more prone to loss of bone density as they age than men, it is no longer considered a disease exclusively of females. Newer statistics demonstrate approximately one-third of Caucasian and Asian men over the age of 50 may also be affected. Additionally, the percentages for “Hispanics (23%) and blacks (19%) are lower”, but still concerning.2

Diagnosis

Despite the risk for bone loss as women age, asking for a bone density test may not be easy. Testing is expensive, and insurance companies may be hesitant to pay for the exam. Unfortunately, even as you are reading this article, your body is busy replacing old bits of bone cells with new ones, and for many of you, the bone bank could be slightly overdrawn, producing brittle, porous bones. But healthcare weighs the cost of testing and projects that cost against subsequent savings. Experts disagree on exactly who needs bone mineral density testing; it has been hypothesized that 750 tests of women between the ages of 50-59 would need to be completed to prevent one spinal fracture over a 5-year period. Insurance companies then evaluate those studies and decide who meets criteria for bone mineral testing. 2

Currently, criteria established by the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommends testing for:

-

-

- Postmenopausal women who have had a fracture

- Postmenopausal women younger than 65 with 1 or more risk factors, who are also of thin build

- Women 65 or older2

-

T-scores

Diagnosing bone density requires a woman to undergo a painless, noninvasive test called a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan that measures the mineral density of bone. The measurements derived, known as t-scores, then determine which category of bone density the patient falls into (where they land on the mountain slope): normal, osteopenia, or at the bottom of the mountain, osteoporosis. Fracture risk increases the more porous the woman’s bones become (or the more negative the t-score number is reflected on the scale).4

For example, one study published in JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association) reported that a 50 year old white woman with a “t-score of -1 has a 16% chance of fracturing a hip, a 27% chance with a -2 score, and a 33% chance with a -2.5 score.” But subtle differences between a -2.3 and -2.5 do not change the risk to your proclivity for fracture. It is your range that is most appropriate for diagnosis and further intervention.2

A t-score of above -1 is normal. Osteopenia is defined by t-scores of -1 to -2.5. The lower the score, the more porous the bone. Scores lower than -2.5 are classified as osteoporosis. DXA scanning typically involves measuring the hips and spine, but patients may not be able to lie flat on a table to have the measurements taken. If necessary, the forearm can be measured, or CT scanning can be utilized to measure bone density in the spine. Ultrasound measurements of the heel or forefinger have also been used as a screening tool to identify women at risk for decreased bone density, however t-scores remain the gold standard for diagnosing osteoporosis and osteopenia.3

Your primary care physician may observe additional radiological clues that your bones need exploration. For example, you may have taken a spill and be seen for a routine Xray of an ankle or wrist. The radiologist may observe thinning of the bones, or unusual porosity on the film, and report these findings. If so, these findings may meet NOF criteria for a diagnostic DXA scan.

Treatment

Your physician may determine that medication is appropriate to avoid further bone loss if your t-score is low enough and your risk for fracture remains elevated. Although medications were prescribed more readily a few years ago, they are now being used with more caution as research has demonstrated a few potential side effects, such as a rare occurrence of necrosis in the jaw bone and slower to heal fractures in the thighs of women who took the medication(s) long term.

Medication such as Prolia (denosumab) may be prescribed by your physician if you meet screening criteria, which is diligent. Laboratory values, including blood calcium and renal studies should be evaluated prior to being dosed with denosumab. Denosumab is given by subcutaneous injection and is ordered by a physician. It is typically given in an infusion clinic or MD office as the risk for allergic reaction exists, including hypotension, trouble breathing, throat tightness, swelling of the face, rash, itching, or hives. If doses are stopped or skipped, a risk of broken bones, including fractures of the spine may occur.3

The physician will decide, by subsequent DXA scanning, when it is time to discontinue bone-building prescription therapy. Conservative treatment, such as weight-bearing exercise, calcium, and vitamin D supplementation, should continue as well as healthy lifestyle behaviors. Women should avoid smoking as well as alcoholic beverages.

Conclusion

Although we may take our skeletal health for granted when we are young, we may begin to realize as we mature that our bone bank has been depleted while we were going about the business of living. One day, a snap, a sudden pain, and our supportive skeletal structure has failed us by breaking, demonstrating a porous frailty we never knew was crumbling underneath the flesh. With effective diagnose and intervention, the tools exist to place deposits back into our bone banks, well past our 50’s, if only we recognize what those behaviors might include.

Let us stay at the top of the mountain if we can, keeping our bones healthy and dense, avoiding the slope leading to osteopenia or worse. On that note, I believe I might take a lovely, weight-bearing walk…what about you?

Websites:

- Bones.nih.gov “Osteoporosis: Peak bone mass in women.” National Institutes of Health, last updated October 2018, 800-624-BONE.

- Health.harvard.edu “Osteopenia: When you have weak bones, but not osteoporosis.” Harvard Medical School, Harvard Health Publishing, Updated August 20, 2018.

- Mayoclinic.org “Bone density test.” News from Mayo Clinic, September 7, 2017.

- Uptodate.com “What does bone density do and why is it important?” Finkelstein, J. & Yu, E., topic last updated October 18, 2019, UpToDate, Inc.